(Cross-posted from The Speculist.)

There’s a great piece currently running on Pajamas Media from physicist Frank J. Tipler on the subject of whether our current society any longer has any interest in pursuing big ideas. Not surprisingly, the author of The Anthropic Cosmological Principle opines that there are still some big ideas out there, and that people are still actively and eagerly pursuing them.

He concludes with a huge one. But before he goes there he lays out the following:

Then there is transhumanism: the evidence is very strong that sometime in this century (I predict by 2030, Ray Kurzweil by 2045) we will see the creation of computer programs that are fully equal to humans in mental ability. At roughly the same time, we predict that humans will be able to download themselves into computers, and live forever.

(Yes, you read me right. What you see here is only the second biggest big idea that Tipler presents. Read the whole piece to discover the biggest.)

In the comments section, skeptics make short work of Tipler’s transhumanist projections:

And I predict that by 2030 Mr. Tipler will have revised his prediction of computer programs fully equal to humans in mental ability to 2050, perhaps not noticing that it’s been a good while since anyone takes these recycled 70′s era strong-AI pronouncements seriously anymore. Our gadgets are great tools, and while imputing our own capabilities onto our tools is fun and makes for great movies, it will remain a pipe dream, and thankfully so.

Another adds:

I have seen strong AI claims of this form for 50 years, and they have universally been wrong. We do not have systems that are even close to being able to simulate human intelligence.

I’m not interested in exploring when or whether strong artificial intelligence is going to happen. (Anyone who is interested in the subject might give this a listen.) But I’m intrigued by the argument. People have predicted [name a development] in the past and it didn’t happen when or how they said it would; therefore, predictions of [that same development] can be discounted. Here the principle is applied to strong artificial intelligence, but presumably it will work with anything that has ever been predicted.

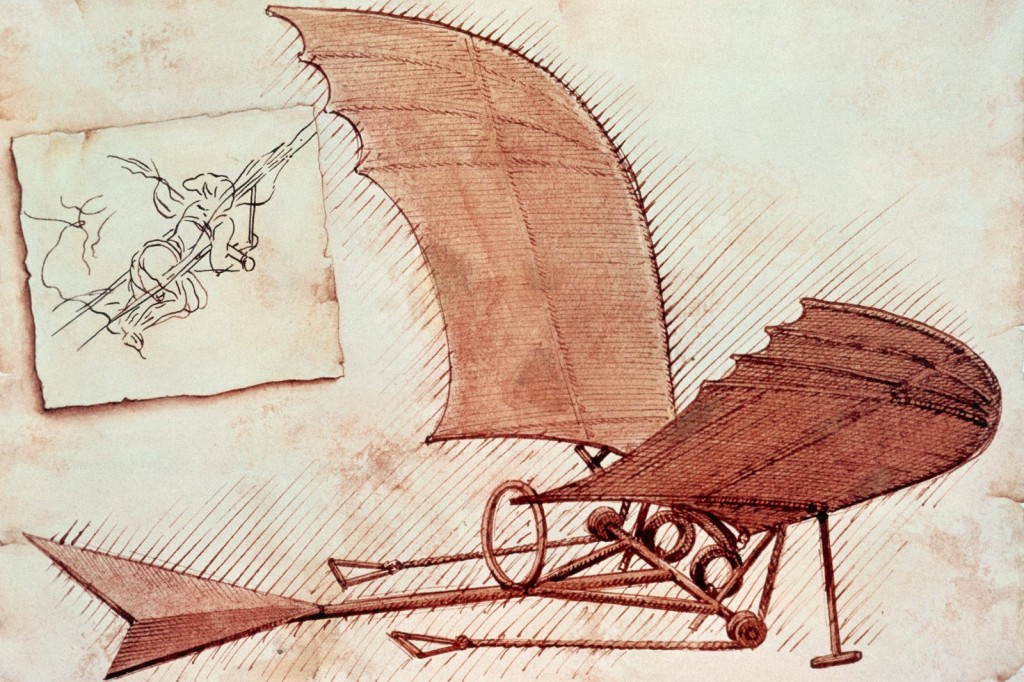

For example, many of you are no doubt familiar with this sketch made by Leonardo da Vinci probably some time in the 1480’s:

This is a preposterously inaccurate representation of how heavier-than-air flight would work. Poor Leonardo naively believed a flying machine could be built from materials available in his day and age. As if! He was off by a mile, as were many who came after him.

Such a blatantly inaccurate record of predictions spanning hundreds of years can only mean one thing: airplanes are impossible. They do not exist.

Oh, and while we’re on the subject, helicopters are also a fantasy:

If you’re not entirely satisfied with that analysis, you might be interested in future forecaster Paul Saffo‘s admonition that we should “never confuse a clear view with a short distance.” I would add that we should never confuse a long road with an impossible destination.

A while back I was present at a talk Saffo gave in which he explained this principle using a chart similar to the one shown below. Technological progress and adoption rates don’t follow the straight line we would expect. Rather, progress occurs along an S-curve which encourages overestimation in the early stages and underestimation further along. Or as Saffo puts it, “Technologists can get it wrong twice.”

Saffo provides some great examples of this S-curve in action as it relates to adoption rates of some familiar technologies.

Obviously, the fact that a given technological development has been inaccurately predicted doesn’t prove it will happen. The point is that it’s not terribly good evidence that it won’t happen, either.

Keep that in mind when you hear predictions of coming developments. Do they sound overly enthusiastic? Do they sound overly cautious? And remember the S curve.